DAVID BURDOWSKI

- Home

- DAVID BURDOWSKI

SANTA MONICA, CA JUNE 9, 1995

DAVID BURDOWSKI

INTERVIEW BY ROBERT CLARY SPIELBERG SHOAH COLLECTION

Camps where David spent time:

Poznan, Buchwerder Forst, Kistrin Neustadt, Jaworzno, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Lagisza, Gleiwitz, Gross Rosen, Blechhammer, Buchenwald, Dachau, Feldafing DP camp

Interview Begin Here:

Robert: Tell me your first and last name and spell it. And, tell me where you were born and when you were born.

David: My name is David Burdowski. I was born in Klodawa, Poland, December 12, 1924.

Can you spell Klodawa:

Klodawa.

R: Tell me what you remember about your childhood. If you remember anything about your grandparents on each side. Your father and mother. What kind of life they had.

D: My mother was born not in Klodawa. [He later recalled the town was Lubien] My father was born in Klodawa, I think. That I’m not sure, either, but I think he was born in Klodawa. As far as I can remember, we had a store. We used to sell pots and pans. Life was kind of normal—a Yiddish life, a Jewish life. They were religious. I had to wear a hat all the time [yamulke]. Friday night we used to go to shul. Friday night and Saturday. Friday night we used a regular Friday night dinner. Shabbos.

R: Which consisted of what?

D: You know!

R: No, I don’t know!

D: Lukshen, chicken. Saturday after shul we usually had “chundt”[?].

R: What was that?

D: That was traditional Jewish food that we put in the oven Friday night, then take out after shul on Sat..

R: What do you remember about your grandparents?

D: From my I don’t remember too much. I do remember one grandmother on my mother’s side—my mother’s mother. She was an older woman. She used to stay with us for awhile. She died, I would say, shortly before the war of normal causes, as far as I know. My other grandparents I don’t remember at all.

R: Did you come from a huge family?

D: Yes.

R: Tell me about it.

D: My father had two brothers in Klodawa. My mother had four brothers in Lubien. That’s where my mother comes from.

R: Where was that?

D: From Klodawa I would say it was about 30 or 40 km.

R: Where is Klodaw?

D: Klodawa is right in the middle of Poland. Anybody who knows where Poznan and Warsaw is, it’s right in the middle of that. We had about 150 km from Warsaw, and about 150 km from Poznan. So, it was right in the middle of Poland, that’s where Klodawa was. And, small little towns. Consisted of about 1000 Jewish families [I’m not sure if he meant all the neighbouring small towns—Konin, Kolo, Kutno, etc., OR 1000 Jewish people of the 350 or so Jewish families IN Klodawa].

It was a normal, I would say, normal Jewish life. I went to school, a Polish school. After school I went to Cheder. Only one year we had a strictly Jewish school, but the city could not afford to keep it.

R: What year was that?

D: I would say that’s about 1934. I must have been about 10 or 11 years old.

R: Then you went to a complete Jewish school.

D: Yes. But, the city could not afford it, so I had to go back to Polish school, which I hated it!

R: Why?

D: Because that’s all you could hear, is Jewish remarks. “You’re a Jew.” “You’re no good.”

R: Who said that?

D: The Polish kids. First thing in the morning you had to say the Polish prayer, even if you didn’t want to say it. You heard it every day. We were not FORCED to do it, but we had to stand up and listen to it every morning as soon as we got into school.

R: Were there a lot of Jewish kids in your school?

D: No, not too many. In my particular class, maybe we were about 40 kids, and 5 or 6 Jewish kids.

R: And you stayed together?

D: Yes, we always would stick together. But, we always were deprived of anything. We were not—since I can remember—we were always deprived. We were always reminded that we were Jewish kids. Always!

R: How did that make you feel?

D: Terrible! That’s why for me, as I remember, when I had to go back to Polish school it was a tragedy. A tragedy. Walking home from school was just unbelievable. The kids threw stones at us.

R: How did you react?

D: How COULD you react? We were afraid to do something, to say something.

R: Because they were bullies?

D: Since I remember, since I grew up, I can always remember that I was a different person than the Polish people were.

R: Did you wear your hat when you went to the Polish school?

D: Yes. We couldn’t wear the hat IN school, but after school we put the hat back on.

R: Did you have a lot of brothers and sisters?

D: I had four brothers, and two sisters. I was the youngest. My oldest brother was in the Polish Army. He didn’t have it too bad in the Polish Army because he was playing the trumpet in the Polish Army. He was playing in the band. So, he didn’t have it too bad. He was there for two years in the Polish Army. When the war started, he went back in the Army and he was captured by the Germans, and sent to Germany, because they made a mistake. He wore a tag, and instead of saying “Moshe Burdowski” Marian Burdowki, so he was sent as Polack to Germany-not a Jew.

R: To a concentration camp?

D: No. He was not in a concentration camp in the beginning. He was working on a German farm as a Polack. Six months later, they ask “any Jew here can go home”. Well, he had a wife and two little kids, so he did go home. And, later was later taken to a concentration camp. My other brother, Hersch Burdowski, was a barber. As soon as the war started, I went to work w/ him as a barber. I was with him, and life wasn’t easy. There was no running water. There were no inside toilets. I had to go and bring the water in to make warm water. That’s why I helped out, and I started working with him right away. My third brother, as soon as the started, he went to Russia and became a Russian citizen. In 1941, the last postcard I got from him, was that he was probably going into the Russian army. And, that’s the last time I ever heard from him. My oldest sister stayed home w/ my parents. She went w/ my parents to Chelmno. My younger sister, which was next to me [age], she also went to Auschwitz. Whatever happened to her, I don’t know. She must have been burned also in Auschwitz.

R: Go back to your childhood. I want to know how you felt during the holidays. Was it a happy time for you?

D: Holidays you couldn’t help it. It was happy. We had a normal Jewish life. We would go to the synagogue. How hard our life was I don’t remember, but it was always on Shabbas was always happy time. On Friday night and Saturday, nobody worked. We had a nice shul, a nice synagogue.

R: Far from where you lived?

D: Not too far. It was in walking distance. It was a small town—a very small town. We walked to shul, naturally. Nobody had any ways of transportation. We HAD to walk on Saturday. Nobody rode on Sat.. It was a happy life. The worst thing was going to school, or playing outside. If we were not surrounded by Jews, the Polish kids would ALWAYS attack us. Always! In fact we had a little river going through our town, and I was afraid to learn how to swim. And, I don’t know how to swim even today, because we were afraid to take our clothes off to go swimming, because the kids would steal our clothes, and run away with them. That was the bad time.

The happy time was when we had the Jewish times together. We’d go to shul. In chedar we were safe. That was the happy life, but otherwise it wasn’t so happy.

R: Did you get along with your brothers and sister?

D: Very much so.

R: They took care of you?

D: Well, I was the youngest, so I guess I was spoiled because I was the youngest.

R: Did they belong to any organizations?

D: Yes. There was—my oldest brother belonged to an organization, and my other brother. They all belonged to organizations. I was the only one—I was too young to belong anyplace.

R: Do you remember what kind of organization it was?

D: There was a Jewish—like a library. I guess he was involved there. Then there were Jewish musicians, which they played together, so they belonged to that.

R: Was it a Zionist organization?

D: Yes, Zionist. Definitely. In certain time, it was happy, and certain times it was not so happy. It was a hard life. A very, very hard life.

R: Your mother was a housewife?

D: Oh yeah! She had six kids to take care of.

R: What do you remember about her?

D: She always used to clean and cook. To tell you the truth, if I were to see a picture of my parents today, I don’t know [he begins to cry]. I don’t know if I would recognize them. In my mind, I remember them. But, if I would see a picture of them now, I wouldn’t remember them.

R: You remember them in your mind.

D: In my mind I remember how my mother was, and what my father used to do. But, if I would see a picture of them now, I don’t know if I would recognize them.

R: Did they scold you a lot when you were young?

D: No! Never!

R: Tell me about your Bar Mitzvah.

D: That was shortly before the war. There were no parties! We were just called to the Torah, said your prayers, and that was it!

R: No gifts!

D: No. [laughing] I don’t think so! If we did, I don’t remember any!

R: Were you happy doing it?

D: Oh yeah. It was a happy time.

R: Tell me about Passover.

D: Passover was also—well the only time we got gifts was Hannukkah. And, Hannukah was a special day for me because I was born on Shabbas Hannukkah. So, that was a happy time. We’d get a big gift—maybe five cents, ten cents, something like that. Passover was very religious. There was no bread—strictly matzoh, and the family was together.

R: At your home?

D: Yes, at my home.

R: With all those brothers and everybody?

D: Oh yeah. Everybody was there.

R: What language was spoken there?

D: Yiddish. I grew up with Yiddish first. Then, naturally, you have to go to Polish school, so you have to know both languages right away, Yiddish and Polish.

R: Did you parents speak Polish?

D: Oh yeah. Oh sure. They were religious, but if you have a store you have to speak Polish. But, mostly, naturally, then spoke Yiddish. I could speak Polish when I went to school, but the minute we got home, between the kids, we started right away we started the Yiddish language. Yiddish was the first language, Polish was the second. All the holidays were observed, but the happiest was naturally Pesach, and for me was Hannukkah. We used to get candy, chocolate. That was a happy occasion.

R: Did you spend a lot of time w/ your friends?

D: Yes.

R: Tell me about that.

D: WE used to, after school, we would go out and play together by the schul, there was a little area we used to play soccer. Saturday, for instance, was a happy time, naturally with the Jewish kids, we used to play together. Not too much. To recall it, it’s like in a dream. We always we used to stick together. The Jewish kids would stick together.

R: What happened in the Polish school. Didn’t you have to go to school on Saturdays?

D: No. Sat and Sun there was no school.

R: No school even in the Polish school?

D: No we never went on Shabbas.

R: What about the Jewish holidays?

D: No we didn’t go on the Jewish holidays, either. We were excused to go to school on any holiday.

R: You liked that?

D: Oh yeah. It was a pleasure. Naturally, every kid to not go to school is happy. [laughing].

R: Were you aware of what was happening in Germany in the early 30’s.

D: Yes. I remember at the time when they were telling us about the breaking of the glasss, Kristellnacht.

R: Who told you that?

D: It was in the papers. In the Jewish papers mostly, and also on the radio.

R: You had a radio?

D: We had a little radio. We could hear Hitler, his speeches. Naturally, as much as we were afraid in the Polish school, we knew what was coming. We didn’t realize the threat that the Germans would do. But, I remember that my mother would say that the Germans were in Poland in the first World War, and the Germans were not that bad. The Germans were better than the Polish people at the time. So, they didn’t believe that that would happen. My father, what I remember he told me, that he was four years in the Russian Army.

R: When was that? What time?

D: I don’t know exactly. It was WWI. I don’t remember the date. We all would have gone to Russia, because the Russian borders were open. But, the reason we didn’t go, only my brother went, is because my oldest brother was in camp already in Germany and we didn’t want to leave him here. But, they didn’t believe that the Germans were capable of doing what they did. So, that’s the reason we stayed.

R: When you were listening to the Hitler speeches, could you understand what he was saying?

D: Well, most of the time we could, because Yiddish and German are pretty close together, anyway. So, we couldn’t understand, maybe, everything. But, we know that he’s no good.

R: Were you frightened by it?

D: Naturally. And, possibly if I had been a little bit older, I would have gone to Russia with my brother. And, then again, who knows? Who knows? He didn’t survive. Even when he went to Russia, he didn’t survive, either. And, from the whole family I am the only survivor.

R: Of all your brothers and sisters?

D: Yes, of all my brothers and sisters.

R: And your mother and father?

D: Yes, and my mother and father. Nobody.

R: Tell me what happened when the war started.

D: In 1939, it was September, the Germans came in. Right away the Polish kids, that’s the first thing they learned, one word, “Jude”. They took the German soldiers, and they used to walk around town and show them where the Jews lived. They used to point, and say, “Jude”, “Jude”, “Jude”. Right away they came in, they took everything away from you, and they told you that all the silver and gold had to be given right away to them. And any arms, naturally. And, if you don’t then you’re going to be killed.

R: Who said that?

D: The Germans. Right away. In fact, they took out right away the Polish mayor and killed him, and other dignitaries from the city and sent them to Auschwitz. At the time I didn’t know what Auschwitz meant, but I remember one was burned and killed there. And, the parents—a Polish person—had to send them money to send the ashes back. That I remember. That was in the beginning. Two years later, all the Jews had to move away from the main streets, and live in the back, away from the main streets. That’s the first thing the order was. Two years later, they came in and said, “If one of the family would go to work, they’d leave the family alone. That was on a Monday. Being the youngest, I was 16 years old, I said “I’ll go”, and I went, and they said they were going to leave my family alone. On Wednesday they took my two brothers and my sister, also to camp. I was sent to Poznan camps, which we were working on the Autobahn, which Hitler had in mind to build between Warsaw and Berlin.

R: You mean like freeways, highways?

D: Yes. Two days later they took my two brothers. But, I know at the time we went to a civilian camp, not like Auschwitz. We worked, but it wasn’t like—we worked with our own clothes. After six months I was sent to Germany—“Kistrin Neustadt” it was called.

R: What kind of job did you do in the Autobahn?

D: Working on the highway. Making the highway. We did leveling the sand. From early morning to late night.

R: How did they feed you?

D: Just a little soup, and coffee, that’s about it. Not enough to live on, not enough to die. But, lucky I was only there for about six months.

R: You were sent there as a Jew?

D: Oh yeah.

R: Did you wear a yellow Star of David?

D: No. We didn’t wear anything. I don’t remember. We were just wearing civilian clothes. And, even if you could run away, where would you run away. We were afraid of the Polish people just as much as we were afraid of the Germans.

R: Was your hair shaved?

D: No. And, from there they sent us to Kistrin Neustadt, which we were working in a paper factory. We were also in a camp. Around the factory was a fence. It wasn’t an electric fence like in Auschwitz, just a fence.

R: Barbed wire?

D: Yes, barbed wired. In the factory we worked 8 or 10 hours a day. And, they fed us enough to live, you know, not to die. You couldn’t get fat on what they gave us. Strictly soup, a little piece of bread, and black coffee.

R: What kind of soup?

D: It was made out of –like a vegetable, kilarie, they used to call it—I always wanted to know how they say it in English—In Germany we used to call it kilirim.

R: Rutebega??

D: I’m not sure.

R: Who guarded you there?

D: The Germans.

R: German soldiers?

D: I don’t think they were soldiers. It was a civilian camp, and civilian people guarded us.

R: Who were the fellow inmates there—the Jews?

D: The Jews. Only Jews. We were there for 1 ½ years. We were there from beginning of 1941 for 6 months in the Poznan camps, then six months later, by the end of 1941-1943 we were in the paper factory. The paper factory was pretty bad. I was lucky enough, I was the only barber at the time. The lager fuher, the main officer, and there was also civilian, and every morning at 7:00 I had to go in there, and I had to shave him, and I had to cut the hair of all our people in the camp. And, being a barber I got a little more soup, or another piece of bread.

R: So, you didn’t go to work? You stayed in the camp cutting hair?

D: I did that, I cut hair, but also, I had to go to work, too.

R: Doing what there?

D: We were about 10 young guys, about 16 or 17 years old, and whenever a train of wood would come in—the made the paper from the wood, whenever the wood would come in, we had to unload the wood from the train. Summer or winter. The winter time, especially, they had the big logs of wood. We had to throw them out from the open trains, then pile them up, and then they came and put it into the factory. One time in the winter it was snowing, when I picked up a log of wood, my finger got caught and I chopped off my nail.

R: You chopped off your nail.

D: Yes. There was a German doctor in the camp, which he used to say, “I don’t know why I’m here, I’m a German, not Jewish!” But, they took him because he was Jewish. There was no medicine, nothing. He treated me and helped me heal that finger. And, that helped me, and I shaved and cut the hair for everybody in the camp, even with that bad finger, so I didn’t have to go to work anymore until Auschwitz.

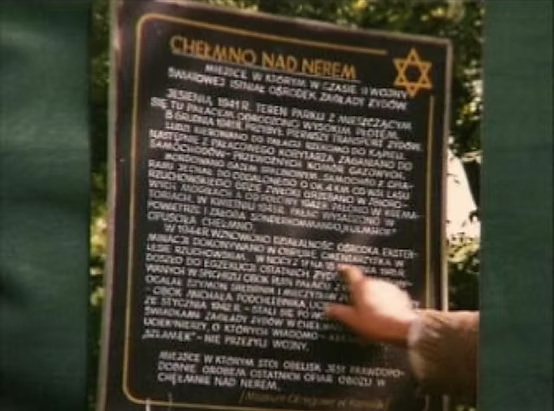

When we got into Auschwitz, that’s when they took everything away from us. In camp, also, we used to get letters from home, and letters from my brother in Russia. That’s why I remember my brother sent me a letter, and said he’s a Russian citizen now, after two years, and they’re going to take him to the Russian Army, and that’s the last I ever heard of him. That was in 1941. And, from my parents, in 1942, I got a letter from my sister, that they are in the church. They took all the young, able people out from the city, and they took all the older people and the kids and whoever was left from the church. They took them from the church—and she wrote me, they KNEW where they were going. They knew they were going to Chelmno. Chelmno, which is just a few miles from my hometown.

R: How do you spell that?

D: Chelmno.

R: And, that was an extermination camp?

D: Strictly a killing camp. But, I don’t understand, I still don’t understand how, or it must have been a Polish person, she gave the letter to them. And, the letter was sent to me. And, we know that in January of 1942 they took everybody out from the city into special made trucks, and they gassed them on the way from the church to the place where they burned them. First, they—from the way I understand as I heard later on, that they took my father and able people, and they had to dig the holes to put the people in to bury them. That was in winter time. Then when summer came, all the bodies were thrown out from the graves. Then they built a crematorium and they burnt them. Everybody. Including my father, my mother, my oldest sister, and my brother’s wife and two kids. And, the whole city, there is nobody left. The only ones who were left were taken to the concentration camps. And, this was in January of 1942.

R: Tell me about your trip from the second camp to Auschwitz. Tell me how it was , and where it was and how you travelled.

D: I didn’t know at the time who they were, but a whole group came into camp. And, I saw already that there were electric wires there before we left Kristin. I saw inmate, like from Auschwitz, with numbers and stripes, but I didn’t know who they were. We couldn’t talk to them, and they couldn’t talk to us.

R: In that second camp?

D: In Kristin, yes. Then one day, I guess it was Eichmann and Dr. Mengele, and a whole group of German officers came into the camp, and a day or two days later they took us on a train, an open train, with German soldiers, and they took us to Auschwitz.

R: How long did you travel?

D: I don’t remember exactly how long, but I think probably one day and a night. It was quite a trip. We didn’t get any food. Nothing.

R: How many people were in the cattle car?

D: I don’t know how many exactly. There was no place to sit down, or no place to lay down. We had to sit like cattle, one next to the other.

R: What were your thoughts?

D: We didn’t know what was happening until we came into Auschwitz. Everybody got out, and I recognize the same man, which was Dr. Mengele. We came in, not to Auschwitz, but to Beikenau. We got out from the cattle cars, and right away they said, “Anybody who cannot walk—there was a truck waiting there—get on the truck.” And, a good friend of mine from my hometown got on the truck. He begged me to go with him, but I said, “No, stay here with everybody else—Don’t go!”. Later on I found out that they took them right away to the gas chamber and burned them. And, then Dr. Mengele was standing there pointing the finger, who should go to the right, and who should go to the left. But, coming from a working camp, most of us were sent to Auschwitz. And, we walked from Birkenau to Auschwitz. In Auschwitz they took everything away. I had my pictures from my parents, and from my brothers and sisters. And, I had the last letter from my sister and from my brother in Russia. And, a Polish guy—all the Polish people were there—I guess they were doing most of the work, and he says, “Give me that”. Then he said, “First of all, take off all your clothes.” “Leave everything here”. “Go into the showers, and when you come out of the shower then you get everything back”. The pictures, all the watches—I had a watch that my father gave me. I kept that. They took that away. The rings, everything. Then I came out from the other side. When I came out on the other side, I didn’t see anything. I didn’t see my pictures. I couldn’t find my letters. I didn’t see anything. Then they gave us the stripes. No, first they took us in after the shower and they cut all the hair off. My hair from my head, all the hair. Then they gave us the clothes with the stripes, and into the barrack. It was Barrack 2 in Auschwitz.

R: What kind of clothes was it?

D: It was nothing but a pair of pants, and I don’t even remember if we had an undershirt, but there was a shirt. Yes, it was a shirt, not an undershirt and a little jacket. No coat. No nothing. And, we were in Auschwitz for maybe a month. Then, by the way, they give us the number.

R: Where in Auschwitz? When?

D: In Auschwitz. Yes, after the showers, and after they took the hair off.

R: Tell me what number it is.

D: 141935.

R: What’s under the number?

D: I really don’t know. I ask a lot of people what they number–.

R: Is it a triangle?

D: Yes it’s a triangle, but I really don’t know what that triangle means. It couldn’t be political because we were not political We came from a working camp, so I really don’t know. Different people say different things about the triangle underneath, but to tell you the truth I don’t know.

R: Did you wear a triangle on your clothes?

D: On our clothes we had our number, and I don’t remember if we had the triangle there or not. But, I know that political prisoners had a triangle only and a number. A big triangle. Anyway, I was in Auschwitz for about a month.

R: Doing what?

D: Nothing. We were counted in the morning, counted at noon, and counted at night.

R: How long did you stay on a roll call?

D: Until everybody was counted for.

R: Long roll calls, short roll calls?

D: Very—sometimes it took an hour, sometimes more. Three times a day. And, also, only once a day, we were fed.

R: What were you fed?

D: Again, a little soup—a little green soup. And, a piece of bread. A slice of black bread, and a cup of coffee, once a day.

R: And, what did you do all day long?

D: Nothing, just lay around. Walk around, just hoping a piece of grass, but we couldn’t even find a piece of grass. Finally, I was lucky enough after a month, I thought I was lucky enough to get out of there, because I knew they were burning people. We could see it. We could see the smoke and we know that they were killing people there. After a month they took us out into Lagisza We were sent there by truck, because it wasn’t too far from Auschwitz. So, we were sent there by truck. We came into the camp, we were building the camp. This was the worst of all the times I was in camps. They put us in a barrack that was only four wall—no roof. It was raining. It was cold.

R: Was it winter time?

D: It was before winter. It was already cold. It was raining. It wasn’t snowing, but raining, ALL NIGHT! ALL NIGHT.. And, we were standing in the barrack, and we were screaming. We were screaming all night long. Finally, in the morning, daylight, they took us out, they counted. We were standing maybe an hour there to be counted. Finally, the gave us a little piece of bread and black coffee, and we were sent to work, digging ditches, stones—bringing stones in,

R: What kind of stones—big ones?

D: Yeah, big ones, small ones. Bricks. That was the worst camp I had ever been in. There was one Volksdeutsch, he was from Yugoslavia.

R: What’s a Volksdeutsch?

D: A German not born in Germany. And, they were the worst, and we had a lot of them there. This guy, we went to work, maybe 30 or 40 people, and he would pick one of them in the morning, as soon as we got to work, and he would torture him all day long. By the end of the day, he would kill him.

R: How would he torture him?

D: By jumping up and down. Hitting him. Didn’t give him anything to eat. Make him work harder. Make him do push-ups. Just torture. Hard to describe the torture that he did. And, every time we went to work we didn’t know if our day is over, or not. If we’re going to be killed or not.

R: Was he a Kapo?

D: No, no. A German. Not a Kapo. One day we went to work, and a Polish woman handed me a sandwich on our way to work, and I took the sandwich from her, and a Kapo saw it. And, when we came into camp, he called my number—we were not a name—and I had to take my pants off and I got 25 lashes on my bare behind. Until I almost passed out.

R: Who did that?

D: A German did that.

R: Were they soldiers? SS people?

D: They were soldiers. SS people, all of them were. 25 lashes on my bare bottom. I had a couple of friends, so they picked me up and took me into the barrack. And, in the morning I had to go to work again, doing the same thing. From Lagisza…

R: How long did you stay there?

D: We stayed in Lagisza, —possibly—we came in there in 1943—possibly a year. In the beginning of 1944 they took us to Jaworzno—the coal mine.

R: Is that still in Poland?

D: Yes, in Poland. Going back to Lagisza I was also lucky. One day it was so cold, and almost freezing, my feet froze, my fingers froze, and up until today I still have my problems with my feet. Any change of weather my feet itch terrible. They took me into the little barrack, it was little hospital, I stayed there until Monday. Monday the truck came from Auschwitz and they took everybody away and they burned them—they gassed them and burned them in Auschwitz. I was lucky enough, when I came in there, it must have been in the beginning of the week, and I remember sleeping there for two nights and two days. When I woke up, and I realize what the place was, and they told me that Monday they’re going to take you to Auschwitz, and who knows what’s going to happen. So, there was a German and he was the main man from the camp.

R: He was the commandant?

D: No, he was a German political. Not an officer. A civilian. A German civilian, and he was in charge of the camp at Lagisza. When I got up from bed, and was refreshed, hungry, naturally, and I started to look for something to eat, a little piece of bread, something, and I told him that I was a barber. So, this man, everyday, I would get up in the morning and shave him, and cut his hair, and everybody inside I started shaving. They brought me a pair of hand clippers, and a razor, and I was lucky enough that helped me to survive in Lagisza But, up until then, the people were dying. There were a lot of Greek people coming in, and they were coming from a very hot climate. It was 80, 90, 100 degrees in Greece, and they brought them into Lagisza and they froze to death. They actually froze to death. Starve to death and froze to death, because they came from a really hot climate.

How I survived, I really don’t know. I really can’t understand, because it was so cold and freezing, and I somehow survived.

R: As a barber, did they give you any more food than the other people?

D: I was lucky enough.

R: In which way?

D: I did get a little more food. I got more food because I shaved and gave haircuts. But, I survived there. This was the worst camp that I’ve been in. Even worse than Jaworzno. After one year of being there, they took us to Jaworzno In Jaworzno

R: It was still a labour camp Jaworzno?

D: Oh yeah. They took us right away to the coal mines. And, on top of that, we had to wear wooden shoes. And, walking in winter on the snow, the snow would stick to the wood, and you were walking on stilts, and walking everyday to the coal mines.

R: How long of a walk was it?

D: About 45 minute walk.

R: Were there dogs guarding you? SS guards?

D: No. We had plenty of SS guards. No dogs. I was lucky enough there, I had a friend of mine from my hometown his name was AVRUM OPOCZYNSKI, and he was there already, and somehow he got me out from the coal mines, and I was the barber in the barrack. There was about 200 or 250 people in the barrack, so I was the barber, and I didn’t have to go to work anymore.

R: 250 people stayed in one barrack? There were no separate rooms?

D: No, no! It was all one open barrack.

R: How many barrack?

D: Three stories high. Sometimes four.

R: Mattresses??

D: No [laughing!] All wood. Not even straw, nothing. Just on wood.

R: Did they give you blankets?

: We had one blanket. Coming home from the coal mines, we had to go into the shower—it was winter- we had to take off our clothes, go into shower, run across from the shower into the barrack, naked, and then inside they gave us the clothes. What clothes? It was a pair of pants..

R: Clean clothes?

D: Yes, clean clothes.

R: Were there stoves in your barrack?

D: Yes, there was one stove in the middle of the barrack. And, we used to steal the coal—a little piece of coal from the coal mines, to bring it into the barrack, and then we heat it, this way, the stove, to heat the barrack. There were times that the Germans found out about it, so we had to leave the coals outside. And, they took it away from us.

But, anyway I was lucky enough to be the barber for the barrack, for the whole barrack. I would shave everybody, just about every day. Everyday, seven days a week, I would shave them and cut the hair. It wasn’t easy, but it was better than working in the coal mine.

R: Were you the only barber there?

D: No. Each barrack had a barber.

R: How many people were in the camp?

D: There was about 7,000 people, I think, in Jaworzno.

R: Big camp?

D: Yes. We were there in Jaworzno. In Jaworzno the same thing, every morning we had to be counted, and at noon we had to be counted. At night, sometimes in the middle of the night they would take us out and counted. One time, there was a group mostly of Polish prisoners, and they dug a hole underneath the electric wire, from the barrack, 27 people. Somehow the Germans found out about it, and they were waiting for them when they were almost through. They hanged every one of them. And, we had to walk around a few times watching them hang in Jaworzno.

R: How were you feeling, then?

D: How can you feel when you walk around and you watch everybody hang? It’s terrible. A terrible feeling. Being so young. In Auschwitz, the same thing, anybody who tried to escape, or they didn’t like, they hanged them. In Lagisza the same thing. In the Lagisza they were so frustrated, they couldn’t take it anymore, they went on the electric wire and they were electrocuted automatically.

R: You saw that?

D: Yes, I saw it plenty of times. And, even in Auschwitz people were laying on the electric wires. They couldn’t take it anymore. And, really, I would like to describe it, but it’s not possible to describe the feeling what happened in the camps. And, the only thing that I can really imagine why I survived, is my age! I was so young! We didn’t think of tomorrow. We just lived life—we lived every day, every minute to survive.

R: Did you have any friends there?

D: Friends from my hometown. We stick together. Usually a few of the young people would stick together. We were four young people coming out of Jaworzno. By the way, in January 17, 1945, they took us out, 10:00 at night, and we walked all night and all day until we’re coming to Katavicz. We slept on the ground, and we were four young guys. We took one blanket and we put it on the ground, and three blankets to cover us up. When we got up in the morning there was at least that much snow on us, there was at least two feet of snow from snowing all night. Somehow we survived that night.

I said Katavicz, but I think it was Krakow. We were laying on the stones, and when we woke up and there was snow on us. Not only that I described from Lagisza you know sometimes when you talk about it, it comes back to you. Not only he killed one person—

R: Who is he???

D: The German. He was a regular SS man, but he was not a commandant, just a young guy, an SS man, he probably belonged to the SS. And, he would talk everyday, and once we got to work he picked up one guy, tortured him all day long, and then he killed him. That was going on for quite a few weeks. In Jaworzno a lot of people even died walking on the way to the coal mines, and even on the way back. Sometimes, when we were working at night, we were chained by the hands, so that we could not escape.

R: Chained where?

D: Chained, one to the other, walking to the coal mines, and walking back, especially at night. In the day time, they knew we couldn’t run away anywhere, and even if you run away the Poles will kill you anyway. Or, take you back to the camp. On the march, there was about 7,000 people when we started walking out. Later on we found out that the Russians come in in the morning, and we were gone. They took us out of there. And, from then on, we were going on the death march, from Krakow across Czechoslovakia, into Germany. In Czechoslovakia, naturally we were sleeping outside, and sometimes even the Germans would want to have a little warm, so we went in and stayed in a barn, in the hay. And, sometimes we would dig ourselves into the hay, and after we were out, then the Czechs, young people would come in with the forks, and start digging, and whoever they found, they throw us down. Three times I ran away, and young Czech boys found me and took me back to the Germans. Anybody who couldn’t walk anymore was killed. And, by the way, he had three times his gun on my head, ready to be killed, and somehow I got up, and kept on walking. And, later on I’ll tell about how I went to his trial in Germany. I’ll tell you about that later.

We walked across Czechoslovakia into Germany. I think the first camp was Blechammer. When we got into that camp, we also got—by the way, on the march we got three potatoes. That’s all we got. Three potatoes each day.

R: How many days did you walk?

D: I really don’t know, but I know we walked one complete night and one day. And, then across Czechoslovakia. I don’t remember how many days, but it was all the way across Czechoslovakia, as soon as it was daylight, and the first camp was Blechammer.

R: How big of a camp was Blechammmer, and how long did you stay there?

D: Not too long, just a short time. It was a pretty bad camp, too. Blechammer, then Gross-Rosen. Again, we stayed there a short time.

R: You walked from Blechammer to Gross-Rosen?

D: No, I think we went on an open cattle train, in winter time. It was all winter time. It was from January until almost May. To be exact, how many days, I don’t know. We went from each camp to camp. It was just torture. Torture.

R: What happened when you arrived in a camp? How did they treat you??

D: They would just throw us into a barrack, and again the same thing. They would count us in the morning, count us at noon, count us at night.

R: You were still 7,000 people?

D: No. There was a lot dead already. A lot of them. By the time we got into Dachau, there was only about 200 people left. But, this was just in Gross-Rosen.

R: How long did you stay in Gross-Rosen?D: Just a few days.

R: How was it there?

D: Terrible. Again, it’s a blank, usually. In some camps I remember details, in some camps I can’t remember what happened there. It’s like a blank. I know that we were always hungry. We were always cold. We always stayed for hours until to be counted. Again, we were sleeping on bunks. They were 3, or 4 stories high on plain boards. Again, the food the same thing. You get a little piece of black bread, black coffee, and again the same cold soup, and the soup consisted of no potatoes, and just water and grass just about. And, from there they took us into Blechammer, and Gross-Rosen. And, from Gross-Rosen, we did something there, I don’t remember, but I think we did some work there. Then from there again, the same thing, hunger and hunger and hunger. And, finally to Buchenwald by train. Four days it took us to come into Buchenwald. Four days, that’s all we eat on the train was the snow that fell on us. That’s the only thing we had for four days. Finally, we came into Buchenwald, and they bombed the camp a little bit, I think and there was no water. No water. We stayed there, I think, naked until they finally fixed the water, and finally we got into the shower, and we got a little hot soup. It was the middle of the day, I remember. And, again once a day. All the time I was in Buchenwald, once a day. And, not only that, we had another problem in Buchenwald. We had a lot of Russian-Ukranians there. They used to give us a little coin. With that little coin, you could get a little soup, and a little black coffee. And, at night, those Russians and Ukranians they would attack us and take away our little coins, because if you have two coins, you get two meals. So, not only were we scared of the Germans, we were scared of the inmates, themselves. And, they knew we were Jews, so they’d attack us.

R: Do you remember the physical place of Buchenwald.

D: Yes, same thing. We were already half dead then, or maybe more than half dead. And, I remember we used to walk around in the camp. There was nothing, just nothing, just waiting to die. Waiting to die. That’s all I remember in Buchenwald. Then, finally, they took us out of Buchenwald, again on the train, to another camp. I don’t even remember the name of that camp. Then, finally, to Dauchau. In Dachau, we were already 90% dead. We were nothing but skin and bones already in Dachau. We were probably about three weeks in Dachau, and again the same thing. A little black coffee once a day.

R: They made you work there?

D: No. In Dachau we didn’t do anything anymore. It was even worse. I wish they would put us to work, it would be better. We were just sitting there waiting to die. That’s all. Finally, they took us out of Dachau, again on the train. When we came out of Dachau they gave us a blanket and a piece of bread. No hot coffee, nothing, just a piece of bread and a blanket. Again, on the train. On the train, I remember, later on we found out that the commander from the train was supposed to take us into the mountain between Germany and Austria, and we were supposed to be shot there. But, later on we found out that the commander knew the end was coming, so he did save us. But, a week or two weeks before the end of the war, the National Red Cross came in, and they gave us little packages. In the packages, there was two packages of cigarettes, and two packages of meat, and piece of chocolate. Those packages were the most dangerous thing that we ever got. Because, people started eating that, and they got diarrhea and they died from it.

R: What did you do??

D: What we did, we found one of the Germans and he needed a cigarette. So, we give him a package of cigarettes, and he gave us a half of his bread. And, somehow we eat a little bit of that bread. Again, we got diarrhea, too, but it wasn’t as bad. But, we didn’t touch the chocolate, and we didn’t touch the meat, and that’s how we survived.

R: When you said “we” you still had friends?

D: Yes, we always stick together, otherwise we could not have survived. Always a few young people we stick together, and that’s how we survived. We covered ourselves together, so we’d be warmer, and then finally April, 22, 1945, the American 3rd Army came in. That’s the first time an American soldier took us into a house, there were no Germans there, they all ran away. So, the only thing that stayed in our stomach was cooked potatoes. And, still we got diarrhea, nothing would stay in your stomach. But, somehow when you eat a potato, somehow…then we swell up. My whole body swell up. It took me about a month and a half before we got back to normal.

R: How did you feel when the American Army liberated you?

D: It was shocking. It was just unbelievable that we survived. It’s hard to describe it, again. You couldn’t walk really. You couldn’t talk. You were nothing but skin and bone. Skin and bone. We couldn’t stand on our feet. It was that bad. A skeleton. That’s what we were. Nothing but skin and bone. And, naturally, it was like the messiah come. The Third Army came in.

R: Where did you go then?

D: We went to that house. We stayed in that house, in Staldacht. The train stopped because there was no more light. The electric train stopped there, and that’s when the American Army came in. From there, the American Army came in, and they told us we were going to go into a Displaced Person Camp. That was another story. We had ENOUGH of camps! So, it took them a LONG time to catch everybody to take us into the camp! As long as we heard about a camp [laughing] we COULDN’T believe it! But, somehow the American Army—they knew what they were doing—there was a lot of Jewish people in the American Army. They started to talk to us in Jewish, and told us what was happening. They told us we’re going to a camp, but we’re going to be FREE! Only you’re going to have your own place there.

R: Do you know the name of the camp?

D: Yes, Feldafing, near Munich, about 35 miles from Munich.

R: How did you like it there?

D: It wasn’t that bad. It wasn’t good, but it wasn’t that bad. It took awhile to get organized. And, again, right away, there were ten barbers. They took one of the barracks and they fixed it up, and became the barber in Feldafing. I was there for four years, until July 15, 1949, then I came to the United States. In Feldafing the biggest trouble was to find who was left alive. That was big problem. [he begins crying]

We knew that our parents are dead. But, I was hoping that my brothers and sister were still alive. But, as other people came into camp, I found out that my brother died in Auschwitz, and my other brother also died in Auschwitz, and that my sister died in Auschwitz. All three of them died in Auschwitz.

R: How did you find out that?

D: From people from my hometown. People that were together. In Feldafing, also in the beginning—[crying] I didn’t have anybody. And, I finally realized that I am alone. That was just terrible. So, we started going to different camps, to maybe find my sister is still alive.

R: Who is we?

D: Myself and friends that were looking for their family, too. We went into Landsberg. Landsberg was also a camp. There were a lot of survivors. We know there was a lot of women there, too, in Landsberg. We started checking that, and I found out there that my sister died. And, it was a terrible feeling [crying], being the youngest, and the only survivor.

R: How old were you then?

D: I was 21. In Landsberg, where I found my wife, and somehow we got together. We realized that she didn’t have anything, and I didn’t have anything. She survived with a sister, and I didn’t have anybody, so we got to know each other, and later on she moved to Feldafing. And, in 1946, June 13th, we got married, in Feldafing—in Munich. We had three kids.

R: Were they all born the Displaced Persons Camps?

D: No! We didn’t have any of kids in the DP camps. In 1949, we came to the U.S. together—my wife and me. My first daughter was born in May 1950. My other daughter was born four years later. My third daughter was born in 1955.

R: What made you come to the U.S.?

D: It’s a good question! At the time, we were talking about going to Israel. My wife had a brother who also survived in Russia, and he went to Israel. At the time, he wrote to us that in Israel it’s very hard—very hard life. Going through what we went through for so many years—at the time, I guess I was selfish. We felt that we deserved, after being left alone—a little bit better life. We knew it was bad there [Isreal], but we didn’t know what to expect in the U.S. either. But, waiting for 4 years in Germany, in Feldafing, we finally got a pass to come to the U.S..

R: Did you have any family in the U.S.?

D: No.

R: Nothing?

D: No.

R: Where did you land?

D: We landed in New York. By the way, before I got off the bought, I still had my uniform—my stripes. I wish I wouldn’t do it, but I threw it overboard. I figure I will start a new life. I don’t want to remember the past. And, in fact in that time we COULDN’T talk about the past, and we DIDN’T talk about the past, until much, much later. I came in here, and, somehow, as a barber, and made a living.

R: Where did you live in the U.S.?

D: First we came into Flint, MI, July 15, 1949.

R: Was it through a Jewish organization?

D: Yes, through the Jewish organization.

R: Did you ask the why they sent you to Flint, MI?

D: No. They asked me “where would you like to go?” They asked me in Munich. The organization was in Munich. They called me in and said, “ Where would you like to go in the U.S.?” I said, “I don’t care.” I remember she said, “Don’t go to New York.”

R: You could have gone to Florida!

D: I could have gone to Florida. I could have gone to California. I could go have gone to anyplace, but I didn’t know about the U.S.. I wish I would have. So, they said, “We’ll send you to Flint, MI.” It was a small town. They were building Buicks and Chevrolets there. He says as barber you’re going to do alright there. As long as I was out of Germany, I was happy. So, I was sent to Flint. [laughing] It could have been to Florida, it could have been to California, and it could have been anyplace. As long as it was out of Germany, Flint sounded good, too. I was a barber there. I had to wait for my barber license for six months. I had to be a resident for six months before I could get a license. So, I went to work in the factory. I worked in the Chevrolet [factory] for six months.

R: Who were your friends there?

D: I was one of the first to come into Flint. So, actually, we didn’t have anybody there. But, there were a few American Jewish people there. They were very nice to us. I can’t complain. There was a doctor there, and a lawyer who were in charge of us. It was OK.

R: All of your daughters were born in Flint?

D: Two daughters were born in Flint. My oldest one, and my second one. Then we moved to Detroit, because my wife’s sister lived in Detroit, so that’s why we moved there. In Detroit, the same thing, I opened a barber shop and started working there. And, then my youngest daughter was born there in 1955.

I was called to be a witness, in 1980, to Germany. And, it was from the camp Legesha. I thought for sure it was this man I was describing—this SS man, who was killing those people. But, it wasn’t him. It was the commander of the camp. As soon as I walked in, I recognized him, and I described everything—what had happened there, and what he did. Again, I was called in 1986, and it was the man who had the gun in my head for three times. And, as we walked, and we couldn’t walk anymore, he was killing the people. There were about 200 people in the room. There were seven judges, seven lawyers. I testified what I knew about him, what he did, and how we walked. At that time, [1986] I probably remember a lot more than I do now. I described everything, and afterwards he said, “Now get up, and see if you can recognize this man.” And, I said, “After so many years, it’s not possible to recognize him.” He said, “Well, try!”

So, I walked, and finally said, “This is the man.” They couldn’t believe it! How could I recognize somebody after so many years. I said, “HOW COULD I FORGET THOSE EYES WHEN HE HAD THE GUN IN MY HEAD-trying to kill me, if not “I’m going to shoot you!?”

R: What was his punishment?

D: Who knows?

R: You don’t know?

D: I don’t know. Later on I found out—it was in the paper—there was a little write up in the paper that he got a jail term for so long. And, the same thing in 1980. But, twice I was called for those two. The first time, if they had called me for the man who used to torture those people, and he used to kill those people, I don’t think that I could actually face him, without doing anything. The first time my daughter went with me. At lunch time we were face to face at the door, and I was ready to do something. My daughter could see what was happening, so she grabbed me, and pulled me away, because I was ready. I was thinking, “Should I hit him?” “Should I do something”. But, when she pulled me away, I said, “What am I going to accomplish by hitting him?” “Put myself in the same position as he was, so again, I didn’t do anything.

Going back, after the American Army came in, all the Germans—when we were on the train—they all got drunk, and the American Army came in. They left their guns laying there. I could have picked up their guns and killed them. But, I guess it wasn’t in our system. We couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do it. We were just like cows going from one place to another. I could have picked up the guns and killed them, but the guns probably weighed more than I did! Because I was nothing but skin and bones, so even if I picked up the gun, I probably couldn’t have done it anyway.

Walking out from Jaworzno, the coal mine, there was one Kapo And, he was probably just as bad as the Germans were.

R: A Jewish Kapo.

D: A Jewish Kapo.

R: Tell me what a Kapo is.

D: A Kapo was an inmate, just like we are. This man happened to be from Lodz.

R: What IS a kapo. What is his function?

D: He’s supposed to be in charge of that particular barrack. I’ll give you an example. When we came back from the coal mines, we went in to the shower naked. We had to run, and because it was winter time, freezing, we walked into the Camp. He would be standing there on a chair, on a regular chair, and we had to crawl through the chair to see if we’re clean. And, if we weren’t clean he’d hit you over the head to go run back to the shower. That’s a Kapo. [chuckling]. He was torturing everybody just like a German! And, sometimes even worse. When we walked out that night, from Jaworzno there were a lot of people that were stronger than I was, and older, and they killed them right there and then—right on the march killed him.

R: The Kapo?

D: Yes, the Kapo. They killed that guy. Later on I found that out.

R: How did they kill him?

D: So many people jumped on that guy, and they killed him. They cut him to pieces right there!

R: And, the SS didn’t say anything?D: Nothing. That was Kapos. In fact, it was a Kapo that noticed that I took a sandwich from the Polish woman, when I got the 25 slashes on my bare bottom. Also, a Kapo. But, I was so young, and so naïve at the time, who knows if I would recognize him if I would see him. Who knows? There were plenty of Kapos, they killed them after the war. And, the same thing was in Feldafing. There were a lot of Kapos that were recognized in the camps, and they did something—they beat them up. And, the way I understand it, my oldest brother was standing in the line to get a little soup. So, if somebody knows you, they took the soup from the bottom, if they didn’t know you they took the soup from the top—it was just water. So, he said to him, “Why don’t you give to me like you give to everybody else—why do you give me just water?” So, I guess he hit him over the head with the big spoon. From then on, I guess he didn’t feel good, so they took him to Auschwitz and he burned. But, we beat him up, but what good is it already? My brother is dead. And, that’s how we found out later on.

In the U.S., when I was sent to be a witness, that was a big satisfaction for me, too–to go there, and to testify against those Germans.

R: Was it a question of vengeance? Is that why you did it?

D: I would do it again!

R: Was it because you wanted vengeance?

D: Possibly. Naturally, if I could do something to everyone of them who tortured us, and killed us, and kept us in that place. Naturally, it’s vengeance, or whatever you want to call it. I would do it again if it was necessary to go and testify against them.

R: Tell me about your life now—with your wife, your first wife. How long did you stay married?

D: We were married in June 13, 1946. We were together for 37 years.

R: Was she a housewife?

D: Yes, she was a housewife. She was also in a concentration camp. She was also in different camps.

R: She was originally from Poland?

D: Yes, Mezricz.

R: How did she survive?

D: With her sister. Also, they used to work in Scarzio making ammunition. They were beaten up. She had a very bad back. She had an operation on her back here. The first few years were alright. But, later on, the last ten years of her life before she died, she really went through a lot. And, by the way, when they were taken out form Merzicz, on the train, the way she used to tell me, was her mother was killed in her arms going into the train, and she never forgot that. Psychologically, she was in very bad shape.

R: Was she willing to talk to your children about all this?

D: In the beginning, no. We couldn’t talk in the beginning. I remember in Flint, the Jewish people in the synagogue would say, “Tell us the stories you went through.” We couldn’t talk about it. We could NOT talk about it. The worse thing that I can remember [crying], when my kids, both of them came home—we lived in our neighbourhood with a lot of young people. One day they came home, and says, “How come everybody has grandparents and we don’t’?” That was REALLY bad! How can you tell kids what happened to their grandparents? How can you tell them??

R: What do you tell them??

D: Nothing. We just told them that they died. Later on they found out. Later on we told them the stories, but at the time we didn’t feel that they’re old enough to understand. And, why would they live in fear to tell them that their grandparents died. But, it was heartbreaking. “How come everybody has grandparents?” “All my friends”, she said, “have grandparents”. “We don’t have any grandparents”. It was bad, but we couldn’t talk about until much, much later. We started talking about it. When we got together with other friends who went through concentration camps—naturally we stick together. Saturday night we’d get together, we’d play cards, go to the show together, but no matter what, by the end we were back talking about concentration camps. Between us, we could talk about it, but with strangers we couldn’t talk about it. It was heartbreaking.

R: But the children were NOT strangers.

D: But, they were too young. They were kids. How could you tell your kids that their grandparents died in a concentration camp? They couldn’t understand, anyway. But, later on, naturally, now they know. They know everything.

R: What did your wife die from?

D: Actually, from, I would say, 99% from concentration camp. From depression. Her back trouble, and then she didn’t want to live anymore.

R: How old was she?

D: She was 54.

R: How long did it take you to get remarried?

D: A couple of years. Two years later.

R: How did you meet your second wife?

D: I was a good friend to them. In fact, her husband was in the barber shop on a Thursday. I was giving him a haircut, and he had a heart attack on Saturday night. So, we knew each other before.

R: So, your second wife’s husband died, also.

D: Yes, he died of a heart attack. He was also 54 years old. Afterwards, naturally, it’s very hard to be alone. I met her, and we went together for quite awhile, and finally—my in-law’s were involved in it—my second daughter’s in-law’s. They met Margie, and they said, “If you marry Margie I’ll give you my place in Florida for a honeymoon.” [chuckling]. So, that kind of encouraged us to get married. So, we got married. We didn’t make a big marriage, just the family. No friends. Nobody, just the family.

R: How long have you been married now?

D: We’ve been married almost 11 years.

R: Are you retired now?

D: I’m retired. I’m working only three days a week.

R: You live outside of Detroit?

D: Yes, we live in a suburb of Detroit. West Bloomfield. I can’t complain. I was very with my first wife, and I’m very lucky with my second wife. I have a very, very good marriage.

R: Are both of your combined children married?

D: My oldest two daughters are married, and I have four grandchildren. My youngest daughter lives in California. She’s not married yet—I’m hoping! I live for It [laughing] for the day that she will get married! Her son (Margie) son is married and they have two kids. Her daughter is divorced and has two kids. I can’t complain. They’re all one big happy family. They’re very nice to me, and I hope that I am nice to them.

R: Are you very outspoken about the Holocaust these days?

D: Very. Very much.

R: What do you do?

D: Starting—I would go back possibly ten years—I got involved in the Holocaust Memorial Center in Detroit. I am there at least once a week, sometimes more, and I speak to different groups, mostly to school children. Some of them who cannot come to the Holocaust Center, I go to the school to talk to them about the Holocaust.

R: How are you received?

D: Very much. Very, very lovely. I have very many letters sent to me, “Thank you for talking to us”. A lot of them have never seen a “number”. A lot of them have never seen a survivor.

R: Why do you do that?

D: For my own satisfaction. To know that the Holocaust DID happen, and that we should NEVER FORGET, AND NEVER FORGIVE.

R: Do you want to add anything.

D: Like I said, we should NEVER FORGIVE. [crying] Even after so many talks, and after so many hours that I put in, it’s still, I that I have to talk about it. It’s very, very hard to describe the suffering and the heartbreak that we went through. Very hard. It’s very hard to describe a family of four brothers and two sisters, and parents, and I am the only survivor, and I was the youngest in the family. It’s the only thing.

R: I guess we’ll show photos of your family, OK???

D: OK.

Photo #1 [below]—This is a photo made from a Hebrew school in Klodawa. I am all the way to the right, standing. The man above me with the dark jacket survived—Max Rose, he lives in Florida. From the whole picture there are three more survivors who live in Israel.

R: What year was it taken?

D: !934 or 35. 35 I would say.

Time may pass, but memory remains.

In silence, we hear their voices.

In remembrance, we find meaning.