MARK BURDOWSKI

- Home

- MARK BURDOWSKI

NOVEMBER 12, 1995 QUEENS, NEW YORK

MARK BURDOWSKI INTERVIEW

INTERVIEWER: CHANA MAYER.

Transcribed with permission of the USC Shoah foundation and consent of the Mark Burdowski family.

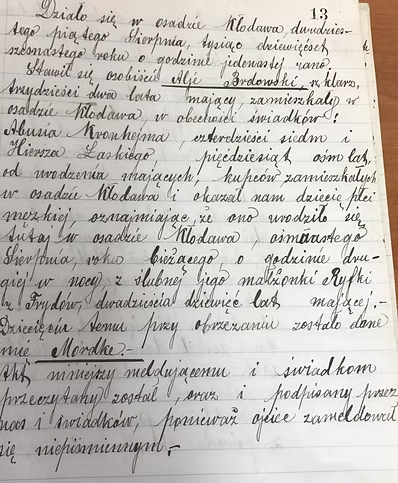

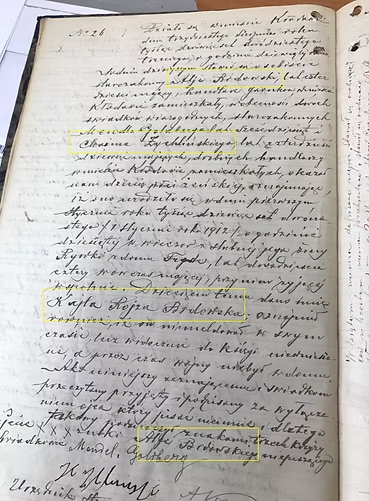

M: My name is Mark Burdowski. I was born in Klodawa, Poland March 6, 1916. I lived there until I went into the army. My father fixed mills [?], he fixed glasss. We stayed in the market and we sold goods. My mother was the same thing. She worked with my father. I had two sisters and one brother [Majer-Hersz].

I met him in Germany [after the war]. He came from Russia [during the war]. He went to Israel. He lives in Israel. My sister, my mother and my brother-in-law are dead. My sister had a baby, then name was Renia, they took her to Chlemno and they killed her. My sister’s name was Yiska, Kyla-Rosa, and my brother was Myer-Hersz. The oldest was my sister. She was married in Kolo to a barber and they had a business. They had a baby. The baby was six year old. The Germans came in and took them away. Everything, and they killed them.

Next was my brother, Myer-Hirsch. When I was growing up, I started working with my sister, a long time. Since the army. In Poland they took you into the Army from about the age of 19 years old. I was an officer in the Army in Posnan for the cavalry—the horses.

C: Before this happened, what was it like growing up in your house? What is your earliest memory of your home?

M: I used to work with my mother. I helped her—with my parents. Later I went—it was not so easy to have a job, so I went with my sister, and I stayed with her. I went to school. I finished my school. I went to a public school. I was 18 years old. Then at 19 I went into the army.

C: Before that??

M: I worked with my sister. She was a beautician, and I helped her. I started to learn. Before I started to work with her, I was a tailor. There were no jobs, so I went to my sister’s and started to help her. Before too long, they called me into the army. I was in the army. I was there for two years, in the Cavalry in Posnan. Before I went home, the war started. I was in the war. When Germany came in, we were fighting. We were in the real war. We ran away. I ran away with a horse. In Warsaw the Germans stopped me and they caught me. They took me to a camp. The whole war in Poland was not too long. I was taught in the Polish Army that if they capture you, try to run away. At night, I see it’s very dark. I dug a hole with [?] the wires and I ran out from that hole. I got to change my uniform, or else they would kill me. So, I ran into a house. I begged them to give me some clothes to change into. She said, “My husband is still not home, so I can give you a jacket, a pair of pants, a pair of shoes..” And, it fit me. I appreciated that, and I told her, “If you have a chance throw out my uniform in the garbage, so nobody will see it.” And, I went out. I went out, in a group. My name was Bordowski, but in the group there was a “Burkowski, Gesaf”. So, I got a paper for him. He was a folksdeutch. He didn’t answer, so I answered, “I am Giswav Burkowski”. They gave me the papers, so I was allowed to walk. It was not allowed to just walk in the night, or the daytime. They would ask you what you were doing. I was a Jew. In the paper, I was a Volksdeutch.

I started to walk home from Warsaw. Came an officer in the road, a Gestapo, and he asked me what I was doing, and to show him my papers. I showed him and he said, “Oh, you are Volksdeutch?” I said, “Yes”. “You know how to ride a horse?” I said, “Yes”. He gave me a horse and told me that I could ride it home, and you can keep the horse. He could take a horse from anyplace. He could take anything he wanted from anywhere. I started to ride it. He was watching to be sure I could ride it. He said, “OK”. I started riding home. It took me 3-4 hours to ride home. I came in to Klodawa. My parents were living in Klodawa, there still was a life. This was right away after the war [started].

I was two days in the house. They came in, and they told me that I had to go away to a concentration camp to work. I said, “OK”. I can’t say no. They took me into to Posnan, to Ramo, this was my first camp.

C: Where was your family?

M: I left my family in Klodawa. There was not one left alive. They took them to Chelmo, small city. They dig themselves alone a grave, and they killed them.

C: How did you find out about this?

M: After the war, some Polish people told me—how they killed them. What can I do?? Not a picture. Not anything. I don’t have anything that’s about my parents.

C: In Klodawa while you were growing up, did you experience any anti-Semitism.

M: Polish people were always very anti-Semitic of Jews. Very Anti-Semitic. When they took all the Jews and sent them to Chelmno they were happy. They took over everything. They took over the houses, the businesses, everything.

C: Do you remember when you were very young, and in school, did anything ever happen between you and the Polish youth?

M: Yes, very anti-Semitic. Very. They can look and find a Jew. They would say, “Jews ?in Palestine”. Even in school. They didn’t like the Jews. Even now there’s nobody there, they’re happy. They took over everything.

C: Was there a large Jewish community in Klodawa?

M: It was a small city, but a large Jewish community. There was a shul. The rabbi of the shul was tied up in a car [forwarding to the war years]. They were dragging him for a couple of miles, he was dead. The Germans did this. This was when the Germans took over the cities [1939].

C: Do you remember going to synagogue with your family?

M: Yes, I remember. Sure I remember. Every Friday, every Saturday we went to shul. And, my mother, too. My mother was 48 years old. My father was 48 years old. I had young parents. My sister was six years old. My older sister was 19 years old, she was married. My brother was one year older than me [Myer-Hirsch].

C: Did you have a Bar-Mitzvah?

M: In Europe they don’t know about “Bar-Mitzvah”. They went to shul and they just got aleya, and this is your Bar Mitzvah. That’s all. This is your Bar Mitzvah day. Not like here.

C: Did you belong to any youth organizations?

M: Not specially. We went to the library when we needed a book. That’s all. It was not special.

C: What big town was it next to?

M: Kolo, where my sister was living. It was not so big, but bigger than Klodawa.

C: Did you speak Polish at home?

M: We spoke Jewish and Polish, but most of the time we speak Jewish. My parents spoke Jewish.

C: Were there other Jews on your street.

M: Where I was living there were about 16 families—a big house. We were left alone. It was a small town, not too much.

C: Did they have any laws against Jews growing up.

M: No, no laws. They just didn’t like the Jews. They would always say, “The Jews should go out to Israel—we don’t need you here.”

C: Did you have family in other parts of Poland.

M: I had a grandmother, my mother’s mother in Kroscnevicz, she was 111 years old. Hitler came in and wiped everything out. My grandmother was very tall, and later she became very small. When Hitler came in the first couple of days, the older people and the young children he took out.

C: Did you or your family know anything about what was going on?

M: We heard that they’re not going to allow us to kill the animals the kosher way—with a Shoket. We knew that something was going to happen. So, for a couple of years, we knew that something was going to happen. The Polish people said, “Don’t be afraid.” We can have a war with Germany.” We can wipe them out.” I was at that time in the Army. We went out in the army with one of my neighbours (Michael Pizer?). All of a sudden it was 3:00 or 4:00 they set an alarm. The Germans started the war with Poland.

C: Before the outbreak of the war, did any people from your town try to leave, or escape?

M: No. They were sitting in the same town.

C: Did anybody believe that—

M: They didn’t believe anything. They believed that nothing was going to happen.

C: What did your family feel?

M: The same thing. We didn’t believe it. We didn’t think that Germany can take over in 24 hours, in 48 hours—they could take over the whole war. We didn’t know that. We didn’t expect that.

C: What happened to your family on September 1, 1939, the day the war broke out?

M: When the World War broke out, we went with a “stencz” [as star] on our hands [arms] a band, that we are Jews.

C: When did that start?

M: It was not allowed to go in the street, as a Jew, with no star.

C: Did that start in 1939.

M: This was in 1939. We were not allowed to go out in the street. They took us in the morning to work, and they brought us back in the evening from work to our homes. That’s all. I wasn’t home too long from the army, in my house. I was only there for about 4 or 5 days. After that, they sent me away to a camp—to Posnan: Ramo. We built that camp.

C: You joined the army voluntarily, or you were drafted?

M: I was drafted. When you are 18 or 19 years old, you get papers that you have to be ready for the army by 19 years old. I went into the army for two years.

C: What year was this?

M: It’s very hard to remember. I was in the army for two years, and when I got out, the war broke out. [so, it must have been 1937-1939—per Michael Pizer the army was an 18 month term]. I couldn’t go home when the war broke out.

C: What were you doing in the army?

M: I was an officer. I was learning how to shoot, and ride horses and all the things you learn to do when you’re in the army.

C: Were there a lot of Jews in the Polish Army?

M: Yes. Anybody who was 19 had to go.

C: Were you able to come in contact while you were [in the army]

M: Yes, I wrote letters home. My father came to Posnan to see how we worked on [in] the street. I was in the army. I was an officer.

C: So, you were allowed to continue contact with your family while you were in the army? Did you hear anything about possible war with Germany?

M: Yes, we were allowed to write home. In the Army we were told that Germany wanted to start a war with Poland. The Polish officers, the General, said, “We’re not afraid.” “We’re going to win the war”. “ We have to be strong.” But, when the Germans walked in, we were in the field, and they started to shoot, we were finished. We ran.

C: Where did you fight?

M: We were fighting all over the cities—up to Warsaw. We were running like chickens with no feathers. We were running away. In Warsaw there was a big fight. They caught me, and they took me the camp.

C: How did they transport you to the camp?

M: In the camp I stayed two days. We had to put all our ammunition down, everything empty, and they took us to the camp.

C: Did you walk there? Was it far?

M: No, it wasn’t far. It was took about a day to walk.

C: Did you know where you were going?

M: No. They told us we were going to a camp. We didn’t know what camp, or what was in that camp. When we came into that camp there was a lot of people. Polish people. Jewish people. All kinds of nationalities. Eating [?] was very bad. I saw it. I said, “I‘m not going to stay here long.” “I’m going to get out.”

C: Was there a selection at that camp.

M: No. I didn’t want to tell them that I was a Jew. I ran away from that camp.

C: So this camp was like a weigh station—a stop-over.

M: Yes.

C: And, then they took you somewhere else.

M: That’s right.

C: How long were you actually there?

M: Two days.

C: Did they give you a uniform.

M: Sure I was in a uniform. I had to get rid of that uniform and run out. I ran out, and I got civilian clothes, and I start to run home.

C: While you were in the camp—what was the name of the camp?

M: I don’t remember.

C: Do you remember where it was?

M: After Warsaw. They don’t tell you the city. They don’t tell you anything. They put in a camp.

C: What did they tell you there. Why did the they tell you you were there?

M: They tell you ONE thing. They tell you if you want to run out, you’ll get shot. If you’re going run away, the wires are electrical. I know how to run away. We were told in the army that if we were ever captured, you have to know how to run away.

C: Did you run away alone?

M: Alone. Yes. I didn’t tell anybody.

C: Did you come with a lot of friends.

M: A lot of friends. They wanted to stay. They were afraid. They said, “I want to live.” Maybe they’re going to send me home.” We were told that if you were ever captured in a camp, try to run out, be careful, and try to be smart. I ran out from that camp.

C: How did you decide to do that.

M: That camp was NOT a camp to live. I was thinking that when I run out they’re going to kill me. But, I want to go home.

C: So how did you escape?

M: I dug a hole. Not to touch the wires. I dug with my hands a hole, a big hole. And, at night, it was about 2:00 at night. In the first house, I knock on the door, she let me in, and I told her what I need. I didn’t know, when I knocked on the door, if she was Jewish or Polish, but she opened the door.

C: She was a Jew.

M: Yes, she was a Jew.

C: How did you dig this hole without people seeing?

M: At night, there was one watch who was watching. It was very dark. In one night, for two hours, I dug the hole, and I got out.

C: As you got down in the hole, you dug more and more?

M: I got through and I start to work at night. I tried to be very careful, and I got out, and I went to this house.

C: How far away was this house?

M: About 20 yards. The house was very close to the camp.

C: Do you think the people in that neighbourhood knew about the camp?

M: Yes, they knew. The Germans came in and walked us to that camp.

C: So the camp was in an area. How did you know the people in that house were Jewish?

M: I didn’t know they were Jewish. I knocked on the door. They let me in, and when I got in they told me they were Jewish, and I told them I was Jewish, too. I need you to help me. I need to get rid of that uniform, and I want to go home. I was wearing my Polish army uniform.

C: Do you remember their names.

M: No.

C: So, how did they help you?

M: They gave me right away civilian clothes, and I told them to throw away my uniform.

C: How far was this town from your home?—

I came home. I found my parents[see above]

My parents didn’t expect anything. In the morning they took my parents and my sister to work. They were working for the Germans, cleaning houses, etc.

I said to my mother, “You take to the bus, and I’ll go to my sister”. I didn’t have the chance to do that. The Germans came in and put me on a transport to Posnan. They came to the house and got me. I went to my sister’s but they caught me. Not just me, but a whole group. They also took my sister and her family in Kolo. They took us in a special truck. We took nothing. No belongings. When we came into camp, there were a lot of Jews already. It took a day and half. You cannot see anything. You do not know where you’re going. When we got there, we started to build the camp. A work camp.

C: Did anybody else know what’s going on?

M: No, nobody knew. After about 10 days there was an appeal to send us into Auschwitz.

C: Had you ever heard of Auschwitz before?

M: No, never. Auschwitz was the biggest camp. Over there came in ALL the transports. We didn’t know what we were going to do there. They took us by train, a closed train—wagons. It took a couple of hours. We came into Auschwitz. They put us into barracks. There was no selection. They took out from the trains, near to the camp. I got a couple of hundred dollars that was hidden in a bread. They took away that bread, they took away our clothes, and gave us the stripes.

When we arrived they gave us ‘Blocks”. A hundred people to Block 10, another hundred people to Block 11. They gave us blocks. I went into that Block, about 80 or 90 people were in that Block. I recognized a lot of people. Many were from my city, from Kutno, from Kolo, from all over—mixed up. Then they give us work, all kinds of work. There was a line to hang people. They liked to hang people. After that they hanged people and they were dead, I had to pick them up and put them in a special room, and they take him to the oven.

C: So, you knew about the crematoriums?

M: I knew. I heard that. I hear that we’re not going to live, that they’re going to kill us. We have to listen to what they’re saying, if not you’re going to get killed right away. Listen to what they’re saying. Work, and do whatever they want and tell you what to do. They took us out about 7:00 in the morning, and we worked the whole day. After Bashtella, they came with soup. You got one slice of bread and soup. They make a soup, and you never see a potato, it’s water—alright, a little warm water. At night, you got at supper time, one slice of bread and another soup. How the soup was made—it was impossible to eat, but when you’re hungry you eat. I didn’t think I could survive more than a week or two. I was a very strong guy. I was very strong, but I didn’t think I would survive. How could I think I wouldn’t survive? I was seeing every day, all day, hanging, killing, get your soap and go and take a shower—it was not a shower it was gas.

C: So you knew about this all right away?

M: Yes, we knew. We knew right away what was going to happen. We knew we couldn’t run out. It was very tight. There was a lot of police around. The Gestapo.

C: There was no selection when you arrived, but did you receive a number??

M: Yes. I have my number. 142, 702 [he rolls up his sleeve to show his number]

This was sitting special people with pin/needles and everybody got this.

C: So while you tried to escape the first camp you were in, you didn’t even try to escape this camp.

M: No. Because there were more gestapos in this camp. A lot of gestapos all around this camp.

C: Do you know anybody who tried to escape.

M: Nobody. Whoever escaped got killed. Whoever ran to the wires, was killed—they were electric. People would get disgusted, so they’d run into the wire. Every morning there was a selection. By selection, I mean—one goes here, one goes here. You don’t know where to go. You don’t know what group goes to work, and what group goes to the oven.

C: Who did the selections?

M: The gestapos.

C: Did you ever meet Joseph Mengele? Did you know who he was?

M: I was in there, but I never met him.

C: Was he known in the camp?

M: Yes. HE was known.

C: How many people were in each barrack?

M: In my barrack there was about 60 people.

C: How small was it?

M: It was no bed, it was a bridge [?bunk] Everybody sleeps together, from the floor to the top.

C: Did people try to help each other, or were they more selfish?

M: People COULDN’T help each other. They got the same amount of food as everybody else. One slice or two slices of bread a day? Nobody got more. Nobody got less.

C: Did you know what was going on outside of Auschwitz?

M: No. Nothing. In Auschwitz you were finished. You knew nothing. You knew ONE thing. Everyday, twice a day, three times a day came a transport from other cities. WE got a pail of soap and we had to divide: “you go in and you take a shower”. That shower meant death. When we went in, we didn’t get the soap, we went to work. This kind of work, from the beginning of Auschwitz, was my work. And, after 15 or 20 minutes, we open the room and we took out the people—the dead people.

C: From the crematorium?

M: Yes. We take back the soap and the pail, and we go to another transport, another group. All of them were burning every morning. Not even a bird could fly in the sky the smell was so bad. The oven was burning day and night. A lot of transports came in every day. Every transport would go into the same room. We would clean this out.

I worked in Auschwitz about six months. Later, they sent us to Birkenau.

C: All six months that you were in Auschwitz, you took bodies out of the crematorium, and down from hanging? You did the same thing for six months?

M: Yes, for six months. We took out from the gas chamber to the oven.

C: How was it that you were transported? How was one transported?

M: You couldn’t say a word to each other. The Gestapo, the soldiers were standing.

You just have to do what they tell you to do.

C: How were you transported from Auschwitz to Birkenau?

M: They took us in a train. It was not far from Aushwitz to the train.

C: Did you know where you were going?

M: No.

C: Did you know why you were transported?

M: I ask you why I got 25 lashes on my behind. You’re not allowed to ask “why”. This word, “why” was not allowed to be said in camp. We came into that camp. I was in Block 6. It was a rotten camp.

C: Was there a selection?

M: Every day.

C: When you arrived, what were you given? What were you told?

M: We were not told anything. We were told that the clothes that we were wearing—they would go in to clean out, and we would get them back. We were already wearing our shirts for 6-7 months without changing. There were not giving us water to wash, and we were afraid to go in for a shower. We knew what would happen if we went into the shower. We didn’t wash ourselves. Our hair [?hand] was dirty and rotten. The worms were eating us up. At night, they would take the shirts and take the worms off, then in the morning you would get back the same shirt. Shoes—we got a long piece of rag, and we wound it up around our feet. This was our shoes. No underwear. We just got pants. The pants were ripped. We got a jacket. The jacket smelled, but was good. A lot of people died at work. We came back from work to the camp, we stay for our soup. We got a piece of bread—one slice, and we got soup—that was plain water.

C: What was your job at Birkenau?

M: My job? Take a stone here, carry it there. Dig a hole here, close up the hole. It was not really work. Impossible to believe that they needed that work.

C: They were making you crazy.

M: Yes, they us crazy. We were not allowed to say “why”. I said once, “why”. They took me in a special room. One SS man held me, and the other SS man hit me. Now you know why! The next day I couldn’t go to work. I was laying under a bed. There was a Jewish foreman that watched us. The foreman was Polchebnik, from my city. He was little helpful. He tried to help the people. The SS man said to him, “Polchebnik, take that man, cover him with dirt, he’s dead”. I was alive. Then the SS man went away, and Polchebnik dug me up, and he hid me. When we went back to the camp, he carried me. The SS man wasn’t there. He carried me to the camp. This was 22, “Bastale 22”. This was the worst job. [Jobs were called Bastale? And were numbered] That job was a death job. When we got back to the camp there was a barrel of water by the Block. If you didn’t walk nicely, or if you said something, they would take you by the leg, with your head in the water, and they’d leave you under the water for a couple of minutes. If you wanted to know why, they would take you again with your head down in the water. And, it was over. You were dead, and they’d throw you in the garbage. This was a whole day.

C: Did they do that to you?

M: I was working that time. I don’t know how I survived! That time I was hit. I was laying for two days in the barrack under a bed. I didn’t go to work. Nobody knew. He was hitting me with a whip that you’d hit horses with. After two days somebody brought me a piece of bread. I was starting to feel a little better. I went out, and I went again to work. He didn’t recognize me. In that camp there was a doctor, Sobnaja. He was a Soviet Jew. He said, “why do you kill them like that?” “Give me one needle and a glass of water, and I can show you how people are dying.” The Gestapo gave him a needle and a glass of water, and he put the needle to the heart. There was a line-up, some people went in, he put the needle in the heart, they walked two feet, and they died.

C: Was he the doctor for the camp?

M: No, he was just in the barracks. He just said to the gestapos, “I’m a doctor. I can show you how to kill people with one needle.” He was not a German, he was a Jew. He killed a hundred people a day with one needle. After the war his cousin, Sabnochia, they reported to the police and they put him in jail. If he’s still alive now, I don’t know.

C: In Birkenau, how long did you do this job—this mindless job of moving stones, and moving them back?

M: A lot of months. A lot of weeks.

C: Were you more or less hopeful in Auschwitz or Birkenau?

M: In Birkenau it was the worst work, what I did. What work was in Birkenau. Every day we took out from all the barracks the dead. There were a lot of barracks, and a lot of people who died overnight. People were dying. We were getting a razorblade to shave them, and somebody took them out. What they were doing with them, we don’t know.

C: You mentioned before a Jewish foreman who helped you when you were sick. Were other Jewish police helpful?

M: No, they were not allowed to help. No, he was from my city. He was a foreman. He would take the people out from the barrack to work, and he watched them. The Germans went around watched everybody. But, at work, he watched everybody. His name was Pochlebnik. He was from my city, and he knew me. He helped me.

C: So, his kindness was an exception to the rule.

M: He made an exception. If they ever found out that he helped me, he would be hanged right away.

C: Did you ever get sick and have to go to the doctors in the camp?

M: There was NO doctor. If you were feeling sick in the morning, you’d go to the ovens. It was not allowed to be sick.

C: There was no hospital?

M: There was a hospital. It was for dead people. They put you in like pigs in a room. The doctor came in, they’d finish you up, and take you to the oven. You were not allowed to say that you don’t feel good. You say that you don’t feel good—you’re finished—it meant death.

C: You knew everything that was going on in the camp. Did you ever overhear the Gestapo over talking about the war and what was happening?

M: No. How can you hear? They didn’t talk because they didn’t want us to hear anything. After I got hit, and went to work with this group, they took me to the “krup” which was an ammunition factory.

C: Was it in Birkenau?

M: Yes, in Birkenau. It was not far. We could walk. We were working with the ammunition. I didn’t work too long there.

C: How long did you work at the ammunition factory?

M: 6 or 8 months. There were two shifts, night and day. When we worked night shifts, a lot of the Germans had a piece of bread in their pockets, and when we worked they let us have a piece of bread.

C: So, there, the Germans overseeing you were a little nicer than usual. A little.

M: This was night time. At night time they were a different group of Germans than during the day. A different type. When they ate, they would specially make sure they had a little leftover, a little scrap. And, we appreciated it. We grabbed it. We kissed their hand. They gave us piece of bread, a piece of soup. Every time somebody else. Not every time the same. [? The same person who GAVE them food, or the same person was GIVEN food—not clear]

C: When you were transferred to ammunition were you a little more hopeful of surviving?

M: No. We were not hopeful of surviving. We were swollen. My legs were swollen. It was very cold. There were no clothes to put on. The worms were eating us. We were dirty and rotten. If we could grab a drop of water, we would wash ourselves with no soap, no nothing. I heard in the camp that they were making soap from the bodies of the dead people. They’re making lamp shades. They’re making gloves. After the war..

C: What happened after you were working with ammunition?

M: After the ammunition we went back to the camp and they told us were going to WALK to Dauchau. We’re going WALK—not ride, but WALK—day and night!

C: Was this the death march??

M: Yes, this was the death march. We walked for a week—more than a week. We walked out from that camp maybe about 5,000 people. There was no eating, no bread, no soup. We stopped every 20-30 miles. We were running around the Gestapo, he was giving everybody a piece of bread. [probably just the soldiers—Mark doesn’t say] We eat snow. It was the winter time. Overnight, they pushed them into a barrack where they hold pigs—I don’t know the English word?

C: A pig pen?

M: Yes. They pushed about 100 people into the pen, and they said you’re going in there overnight, and in the morning we go again. [continue march].

C: Did anybody try to escape?

M: No, nobody. There was no chance to try to escape. The Germans watched us. Behind us were trucks—a lot of trucks. If you couldn’t walk, you would go up on the truck, and they killed you.

C: The Germans were in the truck?

M: Yes. The truck meant death.

C: Did they tell you that you were going to Dachau??

M: Yes, they told us. If you can’t make it to Dachau, you go in the truck. When we were walking we heard a lot of shots—all day. There were a lot of trucks, and if you went in the truck, you were shot. We came in close to Dachau, I couldn’t walk. There were two brothers Denker—they knew me very well—they say, “we’re not going to let you die”. They carried me in under their arms into Dachau. And, they put me under a barrack, and they gave me something to eat. Something. For three days in Dachau, and I ate a piece of what they gave me. When we saw a cat run by, when we saw a dog—we ripped them apart. Everybody grabbed a piece and we ate it. We didn’t cook it. After three days, I heard the Americans came into Dachau. This was the last time. Now, I thought, I have a chance to live.

C: When they carried you into to Dachau, and they just carried into a barrack, does that mean you were not given a barrack? Did the Germans, at that point, didn’t have a selection.

M: No selection. They saw it in the faces. If you were a little weak, you were going in the truck. You can’t walk? We went out over 8,000 people to Dachau. We came in 2,000. All the trucks were filled up with people that they killed on the way. At Dachau they brought them to the oven.

C: Did you know what was going on in the war??

M: We didn’t know anything.

C: What year was this?

M: I don’t know. I had 105 temperature. I had typhus. I was lying under a barrack [bunk?]. If they ever knew that I was sick and I was laying there, they would have sent me right away to the oven. I wasn’t allowed to talk. I was laying and night, not eating.

C: The Germans didn’t know you were there.

M: No. If the Germans knew, they would kill me.

C: How did you recover.

M: When the Americans came in, somebody heard a noise—that here lays a man that’s dying. They took me up out of there, and started working on me. They gave me a spoon of milk every hour or two. They had to give me just a little bit at a time. They started to give me a little soup, a little bread. Then they gave me some needles, and they did an operation, and they kept me alive.

C: You were in Dauchau for a very short time.

M: Very short time, yes.

C: Did anybody know that the war would be over soon?

M: Nobody knew. Nobody knew anything.

C: The two men who kept you alive, who were they?

M: They were two bakers. They died here [U.S] about a two years ago.

C: Where did you meet them the first time?

M: I didn’t meet them, we were together in camp.

C: From the beginning?

M: Not from the beginning, from Birkenau.

C: When the Americans came in, were you aware that meant the war was over??

M: They told me, but I didn’t understand what they meant. I was very sick at that time. I didn’t know anything. I didn’t know that the Germans were out. I didn’t know that the Americans were in. I didn’t know anything. They took me out of there. I started to recover a little.

C: Where did they take you?

M: A special room. Right away they made special rooms to help people. There were doctors. They gave us needles, and they helped us right away. I wasn’t in Dachau too long.

C: How long?

M: I recovered in two weeks when the Americans came in. Later I heard there was a transport to Russia. I went with that transport and it passed by city. I ran down. I was smart enough to run down from the train. I was in my city. I knew where I was. From the train, I walked home. Nobody was there.

C: What did your city look like?

M: The city looked like it did before. A lot of houses down.

C: Was somebody else living in your house?

M: Sure! I was not allowed to go into my house. If I walked into my house, I would get killed.

C: So, what did you do??

M: Somebody told me, “Don’t go in. Don’t ask any questions, just go away”. All the Jews that came back from the camp, they killed them. Why did they kill them? They don’t want to give back to the Jews what they took from them during the war. When we went to the camps, they [Poles in the town] took over everything. Now, when we came, we’d want to take it away again. So, we were told to run away. [indicating the Poles were not happy the Jews came back to reclaim their property] We would not be kept alive if we stayed there. I lived through Hitler. I lived through sickness. I lived through such beatings everyday, and NOW I’m going to get killed? I ran away. I ran away to Lodz. In Lodz I had nothing to do there.

C: Did you want to look for your family?

M: There was nobody there.

C: How did you know that nobody was alive??

M: The people from the city. I talked to one Polish guy right away. He said, “No Jews are alive. Every Jew was killed in Chelmo.” When I heard that I said, “What am I going to do, stay?” “One Jew?” I didn’t want to ask for anything, and I ran away. I came to Lodz. I had nobody there. I had a big family. I had a very rich family, they worked, “Dishka” [?unclear]. Maybe you heard of them? They were very rich. Nobody was alive. I said, “I have nothing to do.” “I have to go back to Germany, there are places for Jews, and then I can go to Israel, or I can go to America.” In the middle of the road, in Czechoslovakia, I met my wife, a young girl. I asked her, “Where are you going?” She said, “I’m going to look for my brothers.” “Somebody told me where my brothers are living”. “One is in a hospital, and I’m going to look for the other.” I asked, “Can I go with you?” She said, “Why not?” At that time I was young. We went on train. We came into Munich. From Munich we went to that camp—where we were before [doesn’t say name]. She found out in ?Golding?? her brother was there. So, we went there, and we found one brother. And, I was staying in that camp. [A photo of the “double wedding” of Mordchai and Majer was submitted by Majer’s granddaughter 11/08. It took place in Feldafing

C: Did you get married in Germany.

M: Her brother went out from the hospital and we made a wedding. A real wedding. He brought flowers. He brought everything.

C: What is your anniversary date?

M: In December. There was a big snow. We were married outside. The Chupa was outside. Then my wife started to work in a kitchen. The cook food and bring to the sick [unclear]. We tried through the organization to try to go away to America. She said she had an uncle in America, and cousins. We came to America. WE had no money, no clothes. Her uncle took us up in their apartment, they fed us. He was a good tailor and he wanted me to work. My wife said, “This is not a job for you.” We are going to try to live for ourselves.” [support ourselves]. We are going to try to get work ourselves. We found downtown on Essex Street, the Lower East Side, we found a room, we borrowed money. We bought that room [rent?]. The first time I went to work, she made a soup. Not like the German soup!!! She made the soup from fish, with some noodles, and I bought a bread. It was living!

C: How long did it take you to move from Germany, in 1945, to America?

M: Not long. Maybe about 4 or 5 months. Not long.

C: Since the Holocaust, since 1945, do you talk about the Holocaust freely? Was it easy for you to be open about it, or did you not want to share the experience?

M: Let me tell you one thing. I don’t have one night sleep— We were away at a cousin’s. I was away with my wife. In the same hour, in the same minute, in the same second, we both start to scream. Screaming in the middle of the night. I was feeling that they want to kill me. It was very bad. Up until now, I wake up at night and I scream. I’m very nervous. I’m a very nervous man. What is screaming? I was feeling that they were killing me, that they were choking me, that they want to hang me, that they want to shoot me. This I have every night in the DP—the nightmares. It’s impossible to believe it.

C: Did you talk to your kids?

M: I talked to my kids. “It’s going to pass,” they said. I talk to my kids. I tell them sometime. They know.

C: One of your jobs in the camp cleaning up the crematorium, and cleaning up of the gas chambers, really made you confront the frailty of life. Every day you were alive, but you didn’t feel so alive.

M: Yes, I saw this every night.

C: How did this affect you??

M: It affected my very bad. I see this every night. I see the hanging. I see the dogs running and ripping people apart.

C: While you were working with the bodies, did you not feel that the people were human, so that you could actually do the work? How did you become so strong enough to deal with that??

M: How did I become strong? An SS man was standing over my head saying, “If you don’t do this, somebody will throw YOU into the oven!” “You have to do what we tell you to do.” “Do not say no!” “Don’t ask why”. “These two words forget.” I was not allowed to say “why”, or “no”.

C: So, really, you distanced yourself because you had no choice.

M: Yes. I had no choice. I wanted to live. I didn’t know if I was going to live, but while you live, you want to see the end.

C: So, Mr. Burdowski, what do you think it is that was inside you that propelled you to continue to try to live, and to continue even though you were in excruciating mental, psychological pain, and physical pain?

M: It’s not easy. I can’t talk to my children about this. I can’t say to my children. Even if they would listen to me, I can’t talk to them about this. I can only talk to my wife. I can say to nobody else. What I got in camp, and I can’t talk to much to my children. I tell them little by little I told them—what my work was, and how it was very bad. I couldn’t work that kind of work. I saw when they cut off a head, and I have to put it in a basket—this was the worst thing for me. But, I had to do it. I had to pick up a whole day of people who had died on the floor—a whole day I had to carry out the dead. I have a friend here, he worked with me Abraham Bierzwinkski [?]—he is not alive. A lot of people who were in my camp together with me, died. I keep telling myself I want to live. I have children. I have grandchildren. I want to see some nachus.

C: While you were in camp, there was obviously no religious life going on, but did you question God? Did you stop believing in God while you were in camp?

M: You don’t have the mind to ask God. You just pray to God, “Let me live”. “Let me try to live”. You don’t know what you’re doing. You don’t know anything. You went to sleep very dirty, very rotten. They wake you up in the morning, you don’t know if you’re going to go to the ovens, or if you’re going to go to work. In the morning they would make a selection: “one here, one here, one here, one here”. And, somebody pushed me, “Go here”, and I went. One time they said, ‘you’ll go here, you’re time has run out.” This was a death line. I went there. The whole time you were carrying on [?] what you were feeling.

C: Since the war, how have you come to terms with everything that has happened.

M: It is very hard for me now to tell you. Sometimes everything comes up. Most of the time you can work. After the camps, and after I came to the United States, I went to the doctor. My son was already born. He said, “You are a diabetic”. I was 50 years diabetic! I took needles for 35 years before I took pills. My sugar goes very high, then very low. If not for my wife, if she didn’t help me, I wouldn’t be alive.

C: So you feel the affects of the war everyday.

M: Yes, this affects me a lot.

C: How have you come to terms with understanding it? Have you ever come to an understanding of what hell you went through, and so many people went through all those years?

M: I talk to people. I tell them what I suffered. I tell them was I passed through. It’s very hard to talk about. When I tell them, I cry. I don’t have a picture of my parents. I don’t have a picture of my sisters. I don’t have anything. I have nothing to show me how they looked. She was the nicest in the city. Like here in the United States they make a queen [Ms. America?—Judy Muratore’s Uncle Michael Pizer told the story of how his sister Kyla-Rosa won the beauty queen prize for Purim and she was a beautiful girl]. I had a nice family. She was the nicest in the whole city.

C: How do you think we can pass this on to future generations, all these messages?

M: It’s not an easy thing. It’s very hard. Tell a child what you suffered. You can’t tell them. I suffered a lot. When I got out of the camp, I weighed 60 pounds! I tried to help myself. How I helped myself, I don’t know how, but I helped myself. I have years to live, and I’m living! I’m 80 years old now, and I live!

C: You seem like you have a very friendly disposition, and you have a very warm smile.

M: I have to have a smile. I have to show people—since I was born, I always have a smile on my face, to whoever I was talking to. I was never mad. I always had a smile on my face. I tried to help people. When I couldn’t help, I couldn’t help.

C: Do you think the Holocaust, or something like it could happen again?

M: It should NOT happen. Now, I don’t believe it’s going to happen again. The U.S. takes care now that it should not happen, that there should be peace. I don’t believe it’s going to happen again.

C: Is there anything that you’d like to tell future generations, and my own generation, so that we can help preserve the memory of your experiences?

M: LOST SOME TAPE HERE-

M: Nobody could tell. From the beginning nobody could tell. We didn’t expect that Germany was going to take over in a couple of hours, the whole world, and kill 6 million people. Not one, but 6 million people went into the oven. There was a city, Lodz, they threw out from the windows small children off a van [?], throw out young children. Old people they took out right away and they killed them. Young children, 9, 10, 15 they threw out from the window! You can throw out your child from a window. The mothers went right away with their children. There were a lot of mothers who killed themselves.

I had a grandmother 111 years old, they killed her. She could have lived another one or two years. You didn’t see a lot of people or young children. Thrown out a window of a big truck.

Now, this generation, they can’t do anything. They can just listen to you, that’s all. We saw it, we were feeling it. How to get over this? It was not easy.

C: Mr. Burdowski, did you see the movie Schindler’s List?

M: I heard of it.

C: Did you see it??

M: No.

C: Do you think these movies serve as a good medium for educating?

M: It’s very good now. Very good. I believe that. It’s not bad.

C: I understand that you have six grandchildren. Do you speak to them about your experiences?

M: Sometimes. Sometimes they listen. They’re very young. They listen they know. We even talk about it, but we don’t talk about it, maybe they can’t sleep. My wife sometimes she goes to the schools and talks.

C: Have you ever gone back to your home town in Poland?

M: No. I would never like to go back. I could go back. I have some property. I have some houses. But, it isn’t worth it. It doesn’t pay. My life is better off, not to take it. The Polish people still don’t like the Jews. All that they got? They still don’t like the Jews.

C: Is there anything that you’d like to add.

M: No. This is enough of what I said.

C: Can you introduce us to your wife?

M: Yes. This is my wife, I married 50 years ago. She helped me a lot. This is Frances Burdowski. In Jewish “Freydala”.

C: It’s very nice to meet you.

F: Likewise, and I hope that everything is going to be remembered.

C: Where do you live.

F: We live in Queens, 80 west 12th 195th st. We are very happy in our own home. With all the suffering that we’ve been through, that’s my home. I tend to hold it as long as possible.

C: I wish you all the happiness together.

F: We do this to show this to the world that exists NOT TO FORGET.

This is my wedding in 1945. I had a very happy wedding.

C: Where was the wedding?

M: In Germany, 1945. It was a very happy wedding.

This is my wife and me. She was pregnant and I was very happy. My son was born. My son Allen.

This is a monument of my city. Everybody who died in the war is written down.

This is a picture of my daughter, my wife, my grandchildren.

Time may pass, but memory remains.

In silence, we hear their voices.

In remembrance, we find meaning.